The Nintendo Game Boy wasn’t powerful, it wasn’t flashy, but it was affordable, reliable, and backed by an army of killer titles like Tetris and Super Mario Land. Naturally, smaller companies tried to ride Nintendo’s wave with their own handhelds.

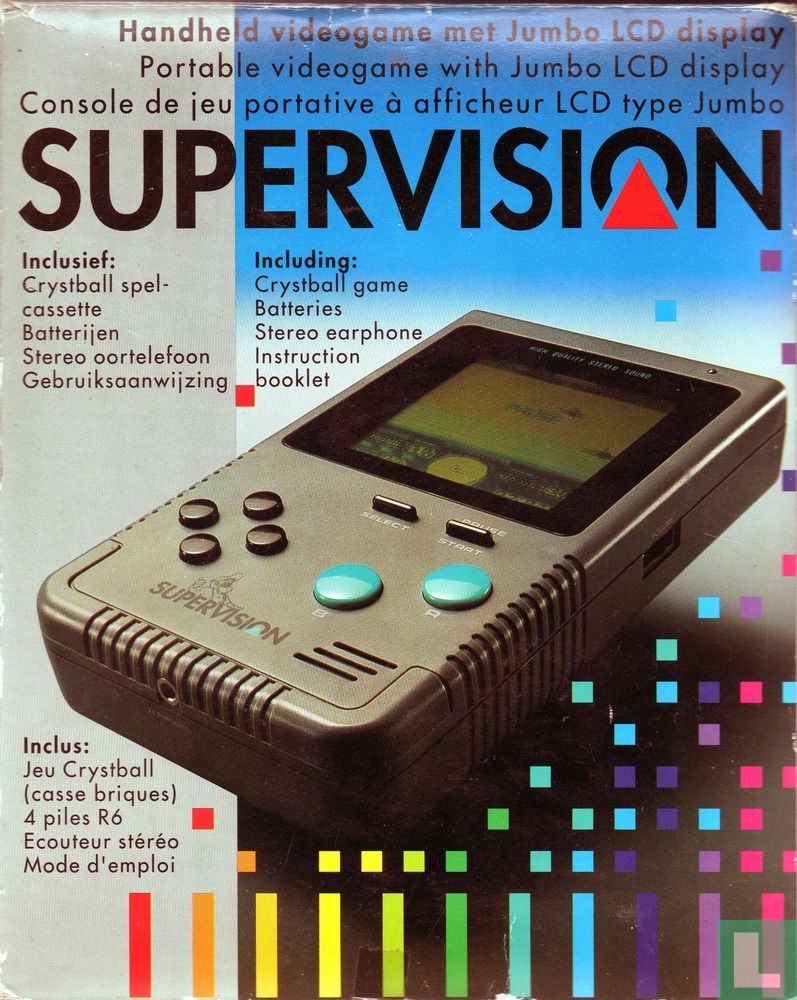

One of the strangest and most ambitious of these imitators was 1992’s Watara Supervision, a Hong Kong–made console that aimed to be “the cheap Game Boy” and ended up as yet another fascinating misfire.

Instead of attempting to compete against Nintendo on innovation, Watara took a low-cost approach to the market, pricing the Supervision at roughly 50% of the cost of a Game Boy. It also gave corporate partners the freedom to create custom branding and packaging for the device, not unlike the Mega Duck before it. In the UK, it was marketed by QuickShot, in Germany, by Hartung, and in France, by VideoJet. In most other regions, they were branded with entirely new names.

Hardware and the Fatal Screen Flaw

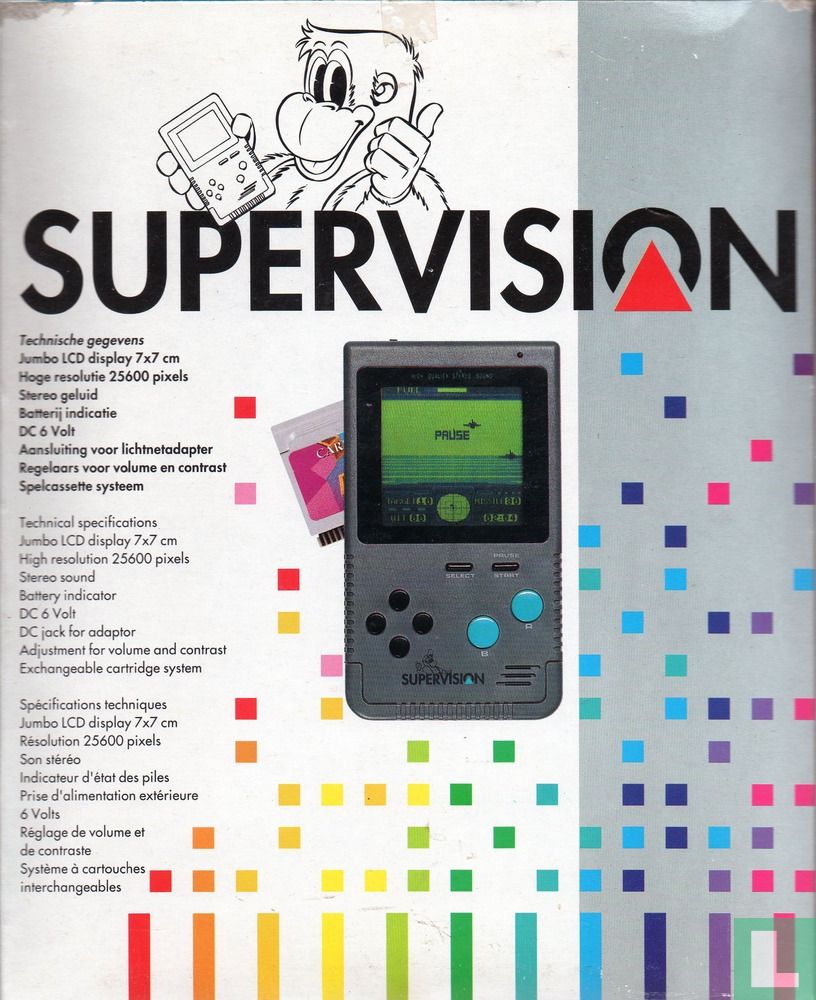

The Supervision was like the Mega Duck in more ways than one. It ran on the same Z80 chip and had the same resolution. Even the cartridges looked similar, though they had a differing number of pins and weren’t interchangeable. The biggest concession to get the Supervision on shelves at such a low price was the quality of the screen.

Watara’s inexpensive LCD panels refreshed slowly and were plagued by severe ghosting, which resulted in sprites leaving behind smudgy trails as they moved. All reviewers of the time concurred that the display of the Supervision was the primary weakness of the product, with one reviewer stating, “the graphics are fine when still, but chaos when moving.”

Differentiation Through Modular Design

Watara tried to differentiate itself in other areas; some versions of the Supervision had a tilted screen that allowed players to change the viewing angle like a mini-laptop. Others had bright, angular casings or TV output capabilities via composite cables, a pretty revolutionary feature in the handheld gaming industry.

The Supervision was modular by design, as Watara granted regional distributors the ability to customize the appearance and packaging. Today, collectors joke that no two Supervisions are alike.

The Game Library: Quantity Over Quality

Although the Supervision had many flaws, the library of available games was larger than several of its competitors. Handhelds like the Hartung Game Master and Gamate often provided only between 10-20 unique games. At the very least, Watara ensured that players would have something to play, even if none of them would go down in history as classics.

A few titles, including Journey to the West and Hero Hawk, attempted to offer narrative and level variety to the game experience, but the poor screen quality made even their best moments difficult to enjoy.

A total of around 65 official titles were released for the Supervision, each on proprietary cartridges. As Watara had no third-party developers for the Supervision, virtually all games were created in-house or by small Taiwanese companies like Bon Treasure. While the results were acceptable, they were uninspiring: simple puzzle games, plain-jane shooters, and arcade platformers that were primarily copies of other popular titles.

The Clone Economy Business Model

Watara’s business model was simple: provide a low-cost, ready-to-brand handheld that distributors could sell under their own logos. In an era before the global standardization of consoles, this approach made sense; we just wrote about a similar story with the aforementioned Mega Duck. Each region could tailor marketing and pricing to local tastes. Unfortunately, it also meant that no consistent identity or marketing push ever formed around the Supervision.

Depending on where you lived, you knew it as the QuickShot Supervision, VideoJet Supervision, Watara Supervision*, or simply “Educational Computer”. More likely, you didn’t know about it at all. The packaging that presented it as an “Educational Computer” mentions math programs that, from what I can tell, never existed.

It was, in effect, another clone economy story, not unlike the unlicensed Famiclones like Russia’s Dendy or Brazil’s Phantom System that became their own modest hits. The difference was that the Supervision was competing in a market with an active Nintendo presence and no killer app of its own. Without that, even a low price couldn’t save it.

What did you think of this article? Let us know in the comments below, and chat with us in our Discord!

This page may contain affiliate links, by purchasing something through a link, Retro Handhelds may earn a small commission on the sale at no additional cost to you.