Tiger Electronics owned the disposable LCD handheld market in 1995, but apparently that wasn’t enough. They wanted in on the head-mounted gaming craze Nintendo had just fumbled with the Virtual Boy. Enter the R-Zone: Tiger’s attempt to convince kids that staring at a blurry red LCD an inch from their eyeballs counted as virtual reality.

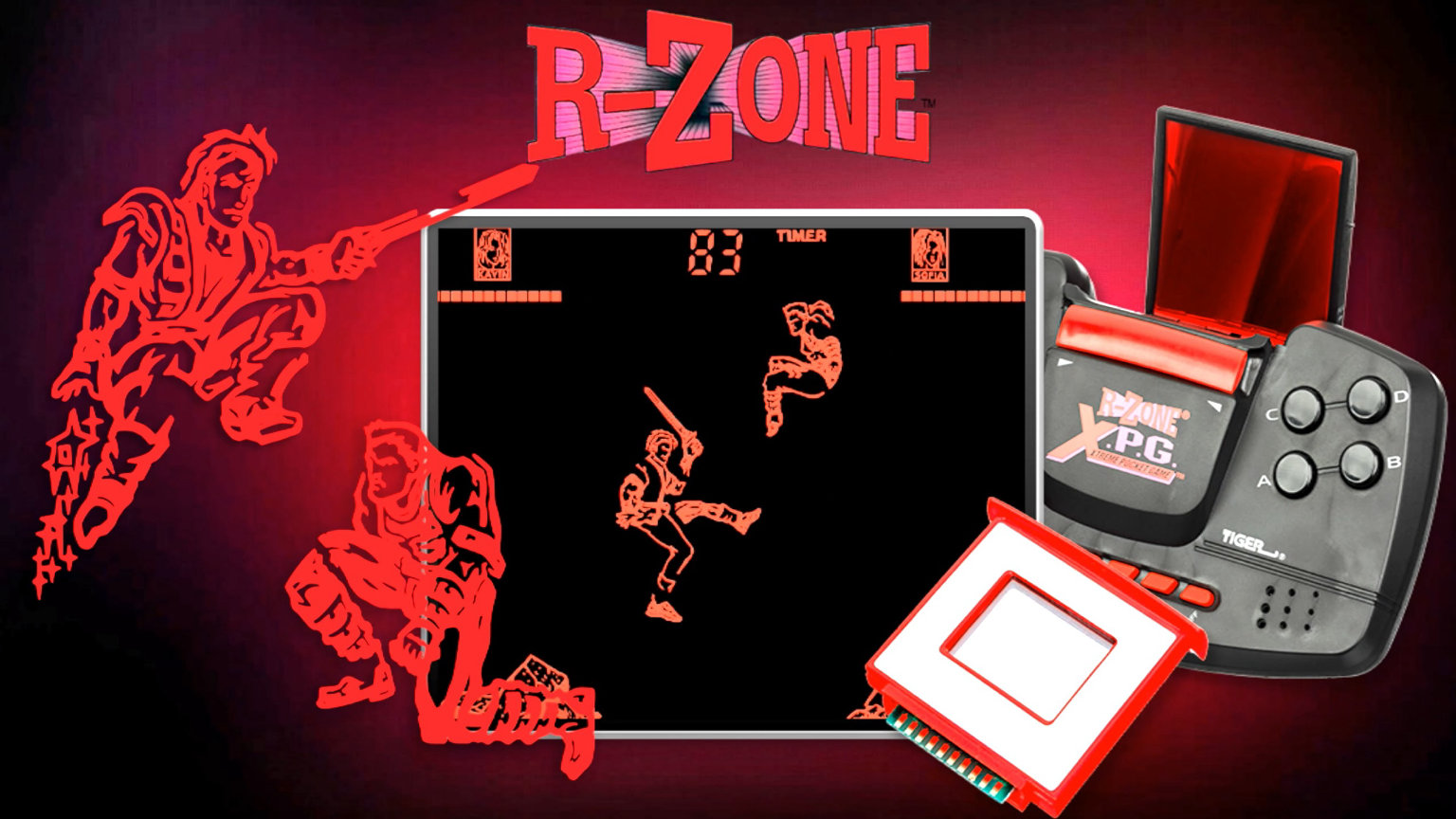

The R-Zone was chameleonic, usable as a headset, tabletop unit, and even a gun-style variant, but the concept was always the same: pick a cheaply produced LCD game, plug it in, and watch Tiger attempt to disguise its trademark beeping calculator displays as futuristic virtual reality. The commercials promised intense action, but the reality delivered a red, flickering stick figure vaguely doing violence, accompanied by a soundtrack of electronic squeaks reminiscent of a smoke alarm.

The hardware itself was equally dire. The original R-Zone was a plastic forehead band holding a flimsy reflective display that you were supposed to align perfectly with your dominant eye. Breathing heavily, turning your head, or blinking too hard could knock it out of focus. Tiger’s official instructions recommended adjusting the headset for “optimal clarity,” a phrase that implied clarity was possible.

Yet, Tiger pushed the R-Zone hard, licensing big-name franchises like Star Wars, Primal Rage, Panzer Dragoon, Virtua Fighter, Batman & Robin, and Men in Black. Unfortunately, each and every one of these properties was rendered in the same single-plane LCD style Tiger used on their $15 handhelds. You weren’t so much playing Panzer Dragoon as watching some red blotches pretend to be dragons while your forehead slowly acquired dents.

Tiger released the R-Zone in waves, each variant supposedly addressing the previous model’s shortcomings while introducing new problems. The original headset version launched in 1995 as the flagship, that infamous red forehead strap with the reflective visor.

It came bundled with Indy 500 and cost around $30, which seemed reasonable until you actually used it. The headset worked by bouncing the LCD image off a small angled mirror positioned over your right eye, a setup that required constant adjustment and made you look like a low-budget cyborg.

In 1996, Tiger tried damage control with three alternative designs, covered extensively in this excellent article from VC&G. The R-Zone SuperScreen ditched the head-mounted approach entirely, turning into a handheld unit with a backlit translucent screen roughly the size of a Game Boy’s display. It was the most usable R-Zone by default, though “most usable” is doing heavy lifting here.

Then came the R-Zone XPG (Xtreme Pocket Game), shaped like a cross between a game controller and a light gun with a flip-up eyepiece. You’d hold it like you were aiming, peer into the viewfinder, and shoot at whatever red shapes Tiger claimed were enemies.

Finally, the DataZone arrived as Tiger’s attempt at legitimacy, a PDA-style device that could supposedly store phone numbers and play games. It was exactly as useful as it sounds. Each model used the same game cartridges, meaning your library of mediocre LCD titles worked across the entire ecosystem of failure.

By 1997, the fate was sealed. Tiger quietly phased the system out, abandoning future releases and clearing stock through blister packs placed near the checkout aisle, where all Tiger products eventually returned to dust.

Today, the R-Zone is a cult relic, a punchline, and a reminder that the ’90s were a lawless era where any company could slap a license on an LCD and call it innovation. Its failure wasn’t subtle; it was literally projected in bright red directly onto your cornea.

Banner image courtesy of EmuMovies

What did you think of this article? Let us know in the comments below, and chat with us in our Discord!

This page may contain affiliate links, by purchasing something through a link, Retro Handhelds may earn a small commission on the sale at no additional cost to you.

4 Comments

I still have an original r zone and a batman and Robin cart. The mirror has broken off but Ive managed to not lose it lol.

Did you ever beat the game? Is that possible?

I bought this when it came out and promptly returned it a few days later. It was exactly as you described, adding nothing over their standard handheld game formula. Clearly a lot of their later attempts you mention manifested themselves in the Game.com which was a mostly better attempt, even if the games themselves still played very similarly to their usual games, just with better dot matrix graphics.

Yeah the Game.com is to Tiger what the Wonderswan was to Bandai. I think both could’ve been great if the companies had more goodwill in the gaming community at that point.